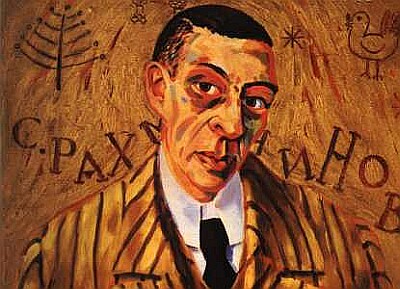

Le Quatrième Concerto de Rachmaninoff

- une fin heureuse ?

par Elger Niels

Musing with Vladimir Ashkenazy.

En 1997, un groupe de spécialistes de Rachmaninoff joint

leurs forces pour promouvoir les concerts, les enregistrements ainsi que

les publications du Quatrième Concerto pour piano de Rachmaninoff,

dans sa version manuscrite. Le petit-fils du compositeur, Alexandre Rachmaninoff

donna une permission spéciale, et cette année, Bossey & Hawkes

publia les manuscrits avec l'assistance de l'expert Robert Threlfall. Ondine

enregistra l'oeuvre avec le pianiste Alexander Ghindin et le Philharmonique

d'Helsinki sous la direction de Vladimir Ashkenazy.

Au milieu de la nuit du 23 au 24 décembre 1917, Segei Rachmaninoff et sa famille traverse la Finlande vers l'Ouest. Rachmaninoff porte une petite valise avec lui, qui contient le manuscrit de l'opéra non terminée Monna Vanna, plusieurs livres de croquis et la partition de "Golden Cockerel" de Rimsky-Korsakoff. Parmi les autres choses interessante, ces livres, maintenant gardé à la Bibliothèque du Congrès à Washington, contiennent des lignes écrites au crayon du premier et du dernier mouvement du Quatrième Concerto pour piano. À plusieurs endroits, les manuscrits sont différents, mais les croquis sont suffisament complets pour supposer que le compositeur a conçu ces mouvements dans leur intégralité avant qu'il ne quitte la Russie pour de bon.

Le 28 mars 2001, 58 ans après la mort de Rachmaninoff et 104 ans après que après la Première Symphonie, le Quatrième Concerto pour piano retourne à la Finlande là où il a été conçu. Dans ce manuscrit de 1926, le Quatrième Concerto pour piano de Rachmaninoff fut exécuté en seulement trois occasions en mars 1927 à Philadelphie. La Première fut un échec et les deux révisions subséquentes, soit en 1927 et en 1941, n'ont pu le sauver. La reconnaissance de cet ovrage arrive seulement avec la renaissance de Rachmaninoff dans les années 1970 et 1980. Par la suite, près de 200 mesures fut retranchées de l'oeuvre et la forme sonate initiale du Finale fut perdue.

La Première en 2001 de Helsinki amène un public de masse au Finlandia Hall. Parmi les célébrités présentes à la première, le compositeur Einojuhani Rautavaara. Pendant le court discours avant le concert, Rautavaara pose une question subsistante à savoir si l'oeuvre du compositeur dans sa forme est complètement légitime. « Pour ma part, j'ai entendu l'original du Concerto pour Violon de Sibélius aussi bien que la 5e symphonie et je ne peux dire que ces deux ouvrages représentent un progrès sur les versions revisée que nous connaissons. »

I had no chance to ask Rautavaara what he thought after he had heard Rachmaninoff's first thoughts, but the premiere was a great success, with the Helsinki audience intensely applauding the musicians and the Helsingin Sanomat headline reading : « Magnificent revival of reviled concerto ». It is clear that the cases of Sibelius and Rachmaninoff's Fourth Piano Concerto cannot be compared just like that. Whereas Sibelius in his revisions distributes musical material to different places, Rachmaninoff's alterations essentially come down to large cuts, a number of minor textural rewritings and only a few newly composed segments to cement a fragmented structure. Why couldn't Rachmaninoff just leave it as it was?

Vladimir Ashkenazy comments : « Who am I to give judgement on a great composer ? Because I really think Rachmaninoff was a wonderful composer, who didn't always compose masterpieces maybe, but whose talent was absolutely unique and beyond description and whose way of communicating was so generous and so unselfconscious. And who am I to judge the fact that he modified and changed some of his music? Many people did. Mahler changed his music all the time. Shostakovich exemplified another attitude to creativity. When he looked at his early pieces he said : "Oh, I do not want to touch it, they are also my children". Beethoven again was different. Before he put his thoughts to paper he went through turmoil. With the Eroica he couldn't quite decide how to start and with the Fifth Symphony again he went through millions of doubts before it was crystallised ».

« Rachmaninoff changed the First Piano Concerto, the Fourth, the Second Piano Sonata and some other pieces too. He was always insecure about his compositions and was quite honest about it. Whenever people suggested something, he listened and very often complied. He said to Horowitz : 'you can do whatever you want with the Second Piano Sonata. You want to cut it here? Cut it here ! Do what you think is right.' Horowitz told me himself .»

Part of the troubled relationship must be ascribed to the way Rachmaninoff's creations were usually conceived. He wrote swiftly and compositions came to him in their entirety : « I go for a long walk in the country. My eye catches the spark of light on fresh foliage after showers, my ears the rustling undertone of the woods. Or I watch the pale tints of the sky over the horizon after sundown and they come - all voices at once. Not a bit here, a bit there. All. The whole grows ». However inconceivable that may be the dating of several manuscripts, references in his letters and evidence from his family and friends support this claim. It might take him no more than two to three weeks - sometimes less - to sketch larger forms. « It came up within me, was entertained and was written down ». By all accounts, the powers of his musical imagination and memory were almost boundless. However, this very facility made him a fastidious composer. Reasonably so, because if music came to him almost instantaneously, so doubts must also have assailed him with equal immediacy, whilst - perhaps even before - committing his thoughts to paper.

In its original version, Rachmaninoff's First Piano Concerto is not a mature composition. It is clearly the work of a student, albeit one that was touched by genius. Gutheil published this version around 1892 but already by 1900, Rachmaninoff felt uneasy about it. He soon forbade his publisher to lend the orchestral material. Just as the opera Aleko was based on Mascagni's Cavalleria Rusticana, the piano concerto closely follows Grieg's Piano Concerto in A minor. Rachmaninoff adopted the entire framework of that concerto's first and last movements and literally built his music into it. Such a procedure is alien to the composer's other concertos, which were utterly original in design and much more suited to the kind of motivic development that was the root of his musical idiom. Rachmaninoff was unable to remove Grieg's traces in revision, but childish echoes of Tchaikovsky were scrupulously erased from the first movement in particular and the Chopin-like finale was entirely rewritten. Ashkenazy likes the later version of the First Piano Concerto much better : « He improved it a lot. It's more effective, concise and not so naive ».

However, Rachmaninoff's second thoughts were not necessarily his best. Ashkenazy is not so convinced by the composer's revision of the Second Piano Sonata. "The way he modified it later, was like deliberately cutting it, to make it more compact and maybe more acceptable if not accessible. But I like the earlier version that shows a real spontaneous composition process."

It was the Dutch pianist Cor de Groot, who, just a few months before his death in 1993, woke my own interest in the manuscript version of the Fourth Piano Concerto. Referring to the 1991 Chandos recording of the second (and first published) 1928 edition of the Fourth Piano Concerto that left me rather unconvinced, De Groot confided to me that he had heard Rachmaninoff himself play that version much better with the Concertgebouw Orchestra under Pierre Monteux. He then went on to recollect that in the early 1950's a former director at Steinway & Sons (was it Alexander Greiner?) told him that the composer had played an even earlier version of the work to him in private. And this version was the real thing. It was, he said, « formally much closer to the Third Piano Concerto » - a claim we can verify today.

After studying all three versions, conducting two and playing one, Ashkenazy has come to the conclusion that in principle he prefers the manuscript edition. « The first movement was always glorious and still is, but the Finale works a lot better with the second subject repeated .» So was Rachmaninoff's Fourth Piano Concerto in its manuscript version simply unacknowledged as a masterwork ? Ashkenazy is more critical : « The thematic material in the Finale is not of Rachmaninoff's best, but that affects all versions of the work, even though he modified it in the last version and made it more compact. With all my love for Rachmaninoff, I really couldn't call it an intense piece of music, although I love it too in a way. " Not one of his best children ", I think, " but I still love it ". »

I am a bit puzzled. Had not Ashkenazy so ardently championed this very Finale in concert and during the subsequent recording sessions, I might well have agreed. « It might have been better if Rachmaninoff had rewritten the entire movement », Ashkenazy says, thinks for a moment and adds with just a hint of a mischievous smile : « And even as it is, what if Rachmaninoff had not cut it up but just modified the end ? Perhaps he could have introduced this wonderful second subject to work it up to a kind of coda - not necessarily as glorifying as in the Third Piano Concerto, but still elegantly (because the harmonies are absolutely wonderful there) and end brilliantly. Maybe that would have made it. »

But why should we crave for a happy end ? Didn't the choreographer Fokine also ask Rachmaninoff to modify the end of the Rhapsody on a theme of Paganini, so that the famous big tune of the 18th variation would return at the end?

« Yes, but I do not necessarily mean a glorious loud end, just a more convincing end. May be it even could have ended pianissimo. What we have now is one of his weakest endings. Perhaps he lacked the inspiration for it. You see, I am looking for a rather emotional explanation that is based on the life he was leading. »

At the outbreak of World War I, Rachmaninoff was called up for military service and being confronted by the vast numbers of men sent out on a hopeless mission, he sensed that there would be no winner to this war. As a prominent musical personality, Rachmaninoff was not risked at the front and in the ensuing gloomy months he set to music religious texts only. The All-Night Vigil opus 37, premiered in early spring 1915, was immediately understood as a profound plea for peace. Unrelated to the massacre of war, the deaths of Alexander Scriabine and Sergei Taneyev, shortly after one another, presented yet another dreadful blow to the cultural front in Moscow.

At this point Rachmaninoff's creative urge somehow became stifled. Thoughts of death tormented him. By the beginning of 1916 the composer's anxiety had developed into an emotional crisis, causing physical pains, most probably of a psychosomatic nature. In May he went off to cure at Essentuki in the Caucasus. His regular correspondent Marietta Shaginian visited him there, handing the distressed composer a notebook full of selected poems for setting. The gift seemed hardly appropriate but then - with rival conductor Serge Koussevitzky acting as an unlikely matchmaker - Rachmaninoff met the young singer Nina Koshetz, a dark-haired beauty.

The extramarital affair that ensued tore the composer between the supreme delights of love, his moral duties as a husband and father and the terrible reality of war in his country. Rachmaninoff's enchantment produced his Songs opus 38 and the Etudes-Tableaux opus 39. As yet, precisely how the affair ended is unknown but it seems rumours of the affair abounded in Moscow and since both parties were married, it is not difficult to deduce the choices that had to be made in the end. Koshetz fired the composer's creative urge. To Rachmaninoff, the loss of Russia was synonymous with the loss of a beloved.

So there may be some point in Ashkenazy's arguing and it is clear that Rachmaninoff certainly pined for lost Russia if not for Koshetz - in his exile he never set Russian poetry to music, whereas he before had regularly written songs. Still, there is clear proof that Rachmaninoff had already finished most of the Finale of the Fourth Concerto upon leaving Russia and the year 1917 definitely was a fruitful period in his creative life. Could it be that Rachmaninoff simply wanted to end abruptly, just as a statement ? Why should the composer start out with a mocking transformation of the Third Piano Concerto's final bars if the message wasn't going to be a harsh one ? Why should a few thunderous bars disrupt the second movement's stillness? And why should Rachmaninoff never have taken up the second subject Ashkenazy is so fond of, and in the final revision of 1941 nearly discard it instead ?

Such questions remain to be answered. If approached with sincerity, music seldom knows right or wrong. It's good to be critical, to listen and think. The more so, since research into Rachmaninoff's music is in desperate need of discerning ears and eyes. Too much has been taken for granted.

And here divergent views merge. Ashkenazy walks toward the piano. "Listen", he says while playing a few chords from the Fourth Piano Concerto's first movement, "I don't know how to explain it correctly but these are not the kind of generous, outreaching progressions we used to hear in earlier works like the Second Symphony. There is no chance of these chords opening up. They are inward, painful, and somehow lamenting." The fascinating thing about the stylistic change Ashkenazy notes is that it didn't start in the composer's exile but somewhere around 1908, long before the revolution was in sight. In one of his characteristic aphorisms, Mikhail Pletnev once said: « There are worlds of difference between Rachmaninoff's Second Symphony and his Isle of the Dead ». Ashkenazy concurs with a few bars from The Bells opus 35. « These are from the second movement. They should be wedding bells, but instead they sound painful. The vocal line soars up, but you feel it will fall to earth again. There is fear also. » The first four notes from the Gregorian Dies Irae provide the motto. That figure is also present throughout the Fourth Piano Concerto. « I love the tension in The Bells. It's enticing in a dangerous kind of way. Love and fear at the same time. That is what real life is about. »

With such inner tensions Rachmaninoff's music became ever more inwardly searching, some would say abstract. There must have been some emotional motif for it but research still hasn't come up with a single explanation. After all, it was Rachmaninoff who said : « Study the masterpieces of every great composer and you will find every aspect of the composer's personality and background in his music ». We obviously haven't studied well enough. The passage from The Bells, Ashkenazy had played starts with the soprano singing i ronyayut svyetly vzglyad na gryadushcheye - [and throw their radiant glances at the future] and there the Dies Irae is hinted at in the melody. Or in Rachmaninoff's final song Dreams an inverted Dies Irae is heard at the words taynikh utyekh - " mysterious consolation ". Yet the Dies Irae isn't always haunting or horrifying with Rachmaninoff. In the Etude-Tableau opus 39 no.8 - which Ashkenazy played like no one else on his 1984 Decca recording - the motif sounds happy and gleeful.

Also in the Finale of Rachmaninoff's Fourth Piano Concerto in its manuscript edition, the Dies Irae isn't always frightening. It prominently heads the glorious second subject that bears some relation - in gestures as well as in its Dies Irae related content - to the even more triumphant second subject from the Finale of Rachmaninoff's Second Symphony. The similarity may not have been intended. A reference to the coda from The Bells concluding the exposition section of the Finale on a fermata sounds more deliberate. None of these thought provoking moments have survived the composer's final edition of 1941.

Stylistic remarks can be made also. From opus 31 onward the composer's writing becomes more motivic and even a touch constructivistic - if the very word is no sin to the Rachmaninoff vocabulary. Upon first hearing the manuscript edition in concert, it struck me how relentlessly it is composed. Especially so in the Finale, where elements can be quite crudely juxtaposed, resulting in a few positively cacophonic moments that do not appear in either of the revisions. Thus the manuscript reveals a missed culmination in Rachmaninoff's development, after which he pulls the classical reigns and presses his thoughts into clearer forms, like those of the Third Symphony and the Symphonic Dances.

Ashkenazy answers with a faint, pensive nod : « You could be right, but then again, I do not believe that Rachmaninoff was a composer who was able to force himself to write in a certain style ». Yet the evolution of a composer's style does not necessarily presuppose forcing matters. It rather requires rethinking and perhaps that is what Rachmaninoff most needed in the end. His muse was silent for years and he started to transcribe, rather than to compose. Then he took up themes for variations and only after the Rhapsody on a theme by Paganini, he seemed to find back his own « theme ».

Ashkenazy and I cannot help pondering the deeper thoughts behind the Corelli Variations. In Rachmaninoff's days the theme was related to a tale of an unhappy lover who wants to drown. One starts to wonder what messages should be heard in these Variations with the 'tormented spirits' from the opera Francesca da Rimini looming large in variation XIX (Rachmaninoff's opera was about adultery and unfulfilled love) and their calm, transfigured coda after an excruciating final variation ? Might this well be the reconciliation absent from the Fourth Piano Concerto ? Certainly, Rachmaninoff's music has not yet been enjoyed to the full.

Ashkenazy waxes enthusiastic over the prospect of a complete recording of Rachmaninoff's transcriptions he is currently preparing as a pianist. « He did the transcriptions brilliantly. I am learning and have recorded already half of them and by the end of this year I'll finish the project. » Even those transcriptions are full of the subtlest Rachmaninovian hints. Nowhere more so than in the arrangement of Tchaikovsky's Lullaby - the very last thing Rachmaninoff ever composed. With a culmination flying away on the peaceful breath of a whole-tone-scale it seems some kind of mysterious farewell. Who had sung this song to him? Was it his sister Yelena who had died so young ? « Or perhaps Koshetz ? » Ashkenazy counters. « ... Yes, Rachmaninoff suffered a lot. Why ? Perhaps we'll never really know. I just cannot help it, I love his work to bits and pieces and I am very happy to have done this ».

Elger Niels(Traduction Tommy Belanger)